LIMINAL REFUGIA

Blue Mountains City Art Gallery, Blue Mountains Cultural Centre, Australia

World Heritage Artist in Residence Solo Exhibition

Curated by Sabrina Roesner

Exhibition catalogue essay by Dr. Ann Finegan

Situated in Darug and Gundungurra Ngurra (Country)

Supported by the Ontario Arts Council

2018

“Abel is a kind of ‘Triassic flaneur,’ a contemporary Situationist whose psycho-geographic experiences are drawn from the action of water on stone, the texture and composition of earth, and the play of the light on the powdery walls of shallow caves . . . Like Timothy Moreton, Abel understands that entities of vast temporal and spatial dimensions, like geological time, nature and natural processes, are too large to be encompassed at the scale of mere human perception. Hence, her method of environmental art practice is to effectively slow time and draw her audience into modes of noticing, moving from studied detail to an understanding of the grander whole.”

Karen Miranda Abel’s Liminal Refugia is an atmospheric, embodied reflection on the deep time interrelationships between earth (stone), water (rain), and fire (sunlight) that manifest in the ancient Triassic sandstone caves of Australia’s Greater Blue Mountains UNESCO World Heritage Area. Highlighting the stability and mysterious purity of these timeless, shrouded ecologies, Abel invites visitors to navigate a sense of temporal elemental refuge—time travel in terrestrial stillness—through resonance in grounded moments of contemplation and visualization of geologic time.

Also known as rock shelters, the shallow sandstone caves of the Greater Blue Mountains differ from deep limestone caves, such as the renowned Jenolan Caves, as they do not possess what is defined in speleology as a “dark zone.” Beyond the undulating portal at the cave mouth, these spaces house what is known as a “twilight zone.” This liminal quality of light and space conjures a sensation of an in-between state—suspension between worlds, between times—in the crepuscular glow of these cloaked environments. Through visitation to such a primeval threshold, it’s as if one momentarily stands in the footsteps of an irrecoverable distance of time, sustaining a prolonged glance at an overarching order of magnitude.

Shielded from the elements yet created by them, the sandstone caves of the Greater Blue Mountains are mainly formed in the Narrabeen strata, sedimentary layers that tell the story of more than 200 million years of intricate and enduring geological history of eastern Australia’s Sydney Basin. Found at the bases and cliff edges of globally significant sandstone pagoda formations unique to the Greater Blue Mountains, these commanding geomorphic structures were sculpted over time by the slow movement of water through stone. This process of cavernous weathering etches the quartz grains from the absorbent sandstone body. Like a mythic hourglass, waves of time gradually deposit a soft mineral bed as the stone hollows: a bone-dry beach harboured beneath the cave’s protective stone arch.

In the rugged Australian bushland, these stone chambers have offered asylum from oppressive heat, bush fire, prevailing winds, and storm events for millennia, constituting vital refugia for humans and wildlife, such as the Rock Ringlet Butterfly, Rock Warbler, Superb Lyrebird, Masked Owl, Sooty Owl, Eastern Cave Bat, Black Rock Skink, and Common Wombat. The dry, shielded nature of these ecospheric interiors have similarly safeguarded galleries of Aboriginal art created on the walls of a great number of Blue Mountains caves hundreds or thousands of years ago—an aspect that continues to shelter the vibrancy of these significant art works today.

Many sandstone caves and encompassing bushland areas are increasingly at risk of being forever changed by large-scale anthropogenic disturbances. Outside of national park boundaries, the impact of underground fossil fuel extraction in unprotected regions of the Greater Blue Mountains shifts the landscape corpus, causing deep vertical fractures that bisect and collapse massive stone pagodas and cliffs, subsequently draining rare hanging swamps and silencing gentle waterfalls. This dramatic image of irreversible destruction vividly contrasts with the protective shield that these same ancient stone structures have offered to delicate cave art works created by humans for millennia.

In the blaze of modernity, it can be challenging to distinguish the sublime primordial rays from the smoldering carbon afterglow. Perhaps more imperative than ever are the reminders offered by intimate geomorphologies that transmit empathic echoes of past worlds and world-views—a humbling clarity lingering in the penumbral twilight of liminal refugia to lift the veil of time.

VEIL OF TIME

Hand-blown glass, raw earth and mineral samples gathered from the Blue Mountains region of Australia by local residents and visitors as part of the GEODIVERSITY project. Permanent collection of the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre, Australia.

VEIL OF TIME

In recognition of the geodiversity and geoheritage values of the Greater Blue Mountains UNESCO World Heritage Area, a constellation of mineral samples gathered by over 65 individuals across the region was ground and finely sieved to create Veil of Time. Unravelling like a geologic time scale, the graduated array of minerals preserved in hand-blown hourglasses evokes the delicate formation of the region’s caves in which rainwater etches quartz grains from absorbent sandstone. This process of cavernous weathering of sandstone cliffs and pagodas slowly releases fine grains of stone as the cave hollow develops, depositing a shoreless beachscape onto the evolving cave floor below.

From December 2017 to February 2018, residents and visitors in the Greater Blue Mountains area were invited to be part of a participatory art project about the geodiversity of the Greater Blue Mountains UNESCO World Heritage Area by gathering a small sample of natural earth from the region. Over 65 community members and visitors in the Greater Blue Mountains region contributed small earth samples thoughtfully gathered earth from around homes, fragrant gardens, bushland, bushwalking pathways, bushfire regeneration areas, and day-to-day places of personal significance. To respect the fragility and intrinsic ecological and cultural values of the World Heritage Area, participants were asked to not gather samples from Aboriginal places or sacred sites, conservation reserves, flora reserves, national parks, state conservation areas, state forests, or other nature reserve areas.

The Earth’s mantle of soil—called the pedosphere—is the thin soil fabric that blankets the ground, comprising natural bodies of mineral and organic compositions, which in the Greater Blue Mountains primarily consist of layers of sandstone, basalt, and shale. Reflecting this mineral composition, most of the earth samples received consisted of sand and clay.

The term “geodiversity” or geological diversity refers to all non-biological elements that shape the Earth: the soils, stones, fossils, geological formations, and landscape-forming processes that are the foundation for all living things, including human life on the grand geologic time scale. Geodiversity is intimately linked with biodiversity and is similarly affected by change. In the Greater Blue Mountains, geodiversity features include magnificent erosional elements such as caves, rock shelters, cliffs, slot canyons, bottleneck valleys, and sandstone pagodas. These ancient forms possess intrinsic values even if they are not the habitat of significant ecosystems.

When considering geodiversity within the context of Australia, it is essential to observe the limitations of this term, as well as English words such as “earth” and “minerals”, which have only existed in the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area for about 200 years. Whereas, six distinct Aboriginal language groups—Darkinjung, Darug, Dharawal, Gundungurra, Wanaruah, and Wiradjuri—have been expressing and caring for Ngurra (Country) in the region for tens of thousands of years. Words that communicate a diversity of complex concepts and intricate knowledge systems related to understandings of earth, minerals, and interconnected natural phenomena in Aboriginal languages were spoken, shared, and lived across this region, and in relation to specific bushland places, thousands of years before English was first spoken in Australia.

In 2000, the Greater Blue Mountains Area was included in UNESCO’s World Heritage List on the basis of biodiversity but not geodiversity due to insufficient evidence at the time. In “Recognising New Values: The Geodiversity and Geoheritage of the Greater Blue Mountains”, Haydn Washington and Robert Wray reveal that more recent scientific research by geologists and geomorphologists presents a strong case for the Greater Blue Mountains to be officially recognized for meeting the criteria of outstanding universal values for both biodiversity and geodiversity (1). Veil of Time is a gesture in support of honouring and protecting the enduring existence of these geoheritage values.

Veil of Time was acquired by the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre for the permanent art collection in 2018. In May 2022, the work was exhibited at the gallery a second time as part of the anniversary exhibition Above the Clouds: 10 Years of the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre Collection.

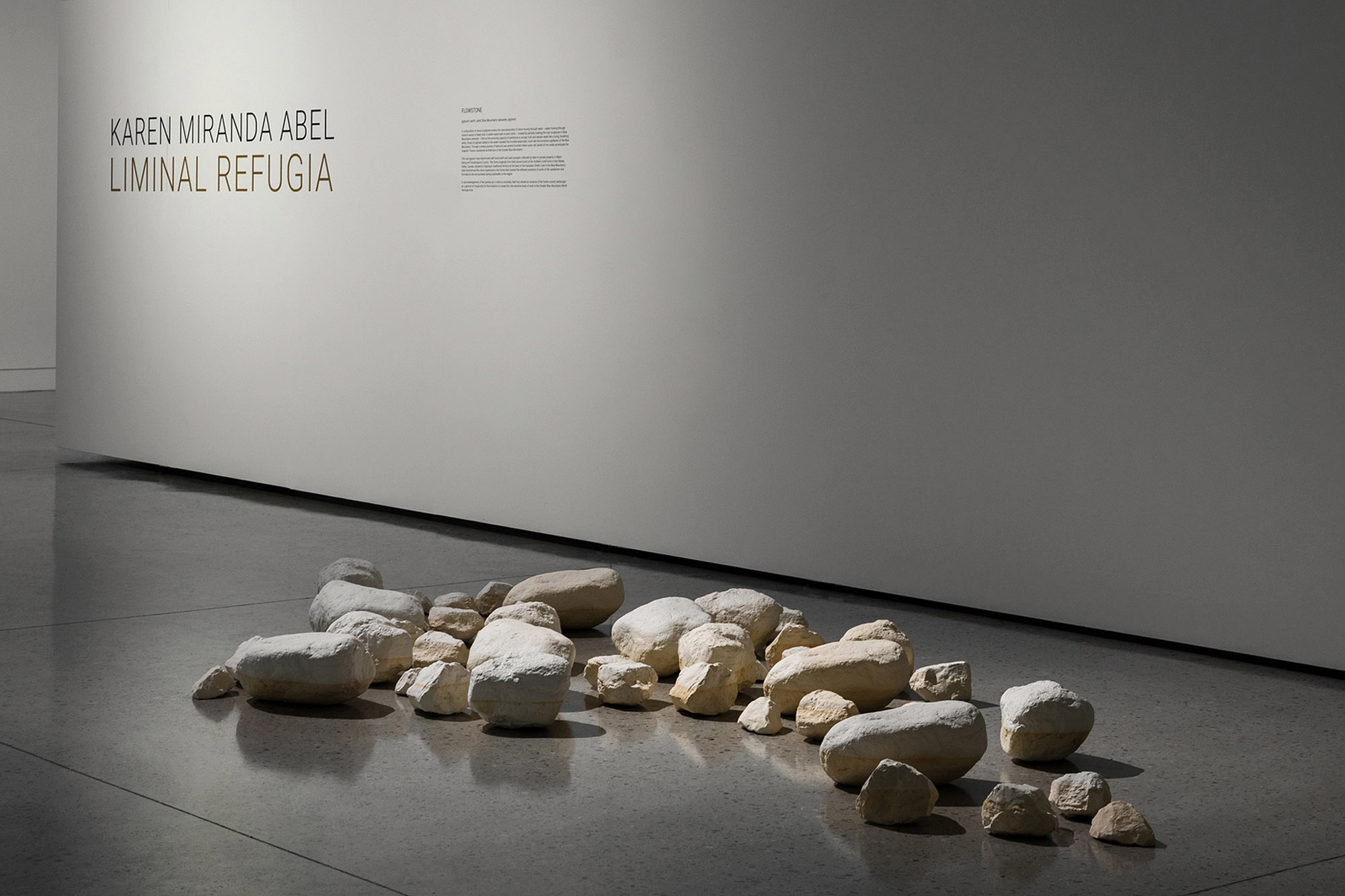

FLOWSTONE (TRIASSIC)

Gypsum, raw earth, sand and minerals, rainwater, natural pigment

FLOWSTONES (TRIASSIC)

A composition of stone sculptures considers the interrelationship between water and mineral in the formation of sedimentary stone across waves of deep time. A subtle watermark—created by partially soaking the cast sculptures in Blue Mountains rainwater—hints at the capacity of sandstone to accept, hold, and release water. Drops of pigment added to the water revealed the invisible watermark, much like the ironstone capillaries of Australia’s Greater Blue Mountains. Through a watery journey of land and sea several hundred million years old, bands of iron oxide accentuate the majestic Triassic sandstone architecture of the Greater Blue Mountains.

The cast gypsum was hand mixed with raw earth and sand collected with permission on private property in Bilpin, Darug and Gundungurra Country, in the Greater Blue Mountains. The forms originate from field stones found at the artist’s mother’s rural home in the Ottawa Valley, Canada, situated in Algonquin traditional territory at the base of the Canadian Shield. Cast in the Blue Mountains, Abel transformed impressions of familiar stones into a series sculptures that resonate the illuminating presence of some of the sandstone rock formations she encountered during bushwalks in Australia.

In acknowledgement of her journey as a visitor to Australia, Abel has shared an essence of her home country landscape as a gesture of reciprocity for the invitation to create this site-sensitive body of work in the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

OCULUS

For over ten days, Abel spent a number of hours a day in a cave in the Wollemi National Park in Darug and Gundungurra Country, informally referring to the site as Oculus Cave. An oculus is an architectural aperture opening to the sky in a domed ceiling or wall that creates an intense sunlight passage.

The daily capsule of time invested at the site allowed for mindful listening to wildlife near and far, and prolonged contemplative observation of elemental cave phenomena such as the rare pools of light that navigate into cave thresholds like rudimentary reverse sundials. A “light pool” is Abel’s term for an ephemeral illumination created when the auric tone of Australian sunlight bleeds its way into the shallows of a cave’s stone chamber. These light artifacts shift and shimmer upon cave walls and floors, composing a dynamic light memory on stone. This primordial interaction of sunlight and mineral matter has likely repeated daily for thousands of years, with seasonal variations created by the angle of the sun.

Abel quietly observed for many hours as the portal of Oculus Cave was activated by light pools and investigated by butterflies, small reptiles (skinks) and a resident Rock Warbler (Origma solitaria). The distinct sound of this individual bird’s wings would echo throughout the stone interior with such frequency that Abel came to recognize it as an intrinsic aspect of the cave’s acoustic ecology.

GARDENS OF STONE

Steel, natural patina created by rainwater and sunlight, water, HD digital video projection (loop). The natural patina was created by leaving the pools outside in the elements in Australian bushland for two months and includes patterns created by wind-fallen eucalyptus leaves.

GARDENS OF STONE

A series of elemental pools reference the undulating portals of seven individual sandstone caves in the Gardens of Stone region located in Wiradjuri Country, Greater Blue Mountains. Locally known by bushwalkers as Michelangelo Cave, Rain Cave, Sand Cave, Cathedral Cave, Acoustic Chamber, Dome Cave, and Cosmic Cave, several of these magnificent stone formations are located in unprotected bushland threatened by coal mining.

The shape of each sculpture is derived from the artist’s personal perspective while situated within the spatial interior of the cave looking out, whereas the gallery visitor is offered the sensation of being outside the cave opening looking in. The generation of this meeting point of perceptual duality suggests a mirrored threshold, a liminal realm of physical and psychological geographies.

The sculptural merging of mineral and water embodies the fundamental relationship between rock and rainwater in cave formation. These geomorphic forms are carved by thousands of years of the slow movement of water through stone.

The sculptures were left outside for a period in Blue Mountains bushland exposed to the region’s heavy rainfall and intense southern hemisphere sun to obtain a natural iron oxide patina, creating a distinct colouration in resonance with the ironstone layers that characterize Triassic sandstone.

GARDENS OF STONE

Detail of natural rainwater iron oxide patina that formed on the bottom of the steel reflecting pools with impressions left by wind-fallen eucalyptus leaves

Photography by Silversalt, Ona Janzen, and Karen Miranda Abel

Exhibition essay

by Dr. Ann Finegan

BACKGROUND

As the 2017-2018 Blue Mountains Cultural Centre World Heritage Artist in Residence, Abel’s site-sensitive field research practice for the culminating solo exhibition Liminal Refugia emerged out of three visits to Australia. This research period constituted over 150 days of living and working in the Blue Mountains from the large studio at Bilpin International Ground for Creative Initiatives. Abel traversed to more than 20 exemplary sandstone caves hidden deep in the distinct pagoda formations of Wiradjuri, Darug and Gundungurra Country. These remarkable sites are situated in the Gardens of Stone and Wollemi National Parks as well as the vast unprotected bushland that lies seamlessly outside of the boundaries of these two official reserves.

As part of a commitment to forming an understanding of the fortitude and fragility of the sandstone caves of the Greater Blue Mountains, Abel invested a period of solitary time in a selection of caves as an intimate study of place, spending many consecutive hours at some remote sites. The hours transpired like minutes in the static cave environment where Abel experienced the form and quality of “twilight zone” light instilled in each stone interior, often wondering when was the last time a human, a woman, spent a similar amount of time in the same cave, if ever.

Remote and off-track, in contemporary times the sandstone caves of the Greater Blue Mountains are, at most, only briefly investigated by a handful of bushwalkers each year. Finding the isolated caves was an extraordinary honour gifted by the generous expertise of Yuri Bolotin, conservationist and experienced bush explorer, who, along with his bushwalking friends, is credited with locating and documenting a number of magnificent caves in the region. Bolotin guided Abel to the cave sites equipped with an innate and exceptionally rare navigational sensibility praised by seasoned bushwalkers as bushcraft.

Intro. Finegan, Ann. "Karen Miranda Abel: Liminal Refugia". Blue Mountains Cultural Centre, Katoomba, NSW, 2018, pp. 1-2.

1. Washington, Haydn and Robert Wray. "Recognising New Values: The Geodiversity and Geoheritage of the Greater Blue Mountains." Chapter 1 in Values for a New Generation: Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area Advisory Committee, 2015, p. 14.

Karen Miranda Abel wishes to express respect and acknowledgement to the Elders, individuals, families, and communities of the six Aboriginal language groups—Darkinjung, Darug, Dharawal, Gundungurra, Wanaruah and Wiradjuri—who are the original and continuing Carers of Country in the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, Australia.

Special thanks to Yuri Bolotin and Rae Bolotin of Bilpin International Ground for Creative Initiatives, Australia

The Blue Mountains Cultural Centre and the Ontario Arts Council are gratefully acknowledged for funding this exhibition