LIGHT GARDEN

Numeroventi, Palazzo Galli Tassi, Florence, Italy

Site-specific exhibition as Artist in Residence at Numeroventi

Supported by the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council

Part of the ongoing body of work titled Elements for a Light Garden

Carrara marble (reclaimed off-cut), flameworked glass, water collected from Tuscan waterfalls, rainwater, solid brass, birch wood

2022

“The metamorphoses generated by space are in addition to those caused by time: the garden—each of the infinite number of gardens—changes with the passing of the hours, the seasons, the clouds in the sky.”

Light Garden is a site-specific conceptual garden of light-cultivating elemental sculptures in glass and marble brought to life with water collected from three waterfalls in Tuscany. Conceived for the courtyard of the historic 16th-century Palazzo Galli Tassi in Florence (1510), the site-sensitive works evolved in two countries: glass sculptures flameworked in Toronto, Canada, and marble from Carrara carved in Pietrasanta, Italy, culminating in an artist residency at Numeroventi to realize the works in situ.

Approaching the courtyard as a contemplative space for quietude and a sanctuary of subtle light and shadow, the works highlight spatial and atmospheric tones, reflecting the life, colour, and Renaissance architecture illuminated by the sky. Attuned to both the enduring and ephemeral characteristics of the space, the installation considers the relationship between the palazzo interior and the ebb and flow of light phenomena of Tuscany—alba (sunrise), tramonto (sunset), crepuscolo (twilight), and chiaro di luna (moonlight)—in resonance with glass cascade sculptures filled with water collected from Tuscan waterfalls, solid glass optical forms, and a marble reflecting pool sculpture at the center of the courtyard.

Alba (sunrise)

Crepuscolo (blue hour twilight)

The marble pool situated on the disused stone puteal (wellhead) at the center of the courtyard was created to collect rainfall and reflect sunlight and moonlight. Hand carved in Pietrasanta from an off-cut piece of statuario (statuary) marble from Carrara, the marble pool sculpture is surrounded by three glass waterfall sculptures suspended on the courtyard walls. The hollow glass cylinders of the waterfall sculptures were filled with water collected from three waterfalls in Tuscany: the waterfall at Grotta all'Onda (Wave Cave), a cascatella (little waterfall) phenomenon streaming naturally from small openings high on a vaulted limestone rock face beside the cave on the summit of Monte Matanna in the lower Alpi Apuane UNESCO Global Geopark in the province of Lucca; a waterfall of Rio Lombricese stream, a small plunge waterfall located downstream from the cave site in a secluded clear blue pool surrounded by trees; and further south in the province of Siena, the terraced cascades of crystalline blue mineral-rich water at Cascata del Diborrato (Diborrato Waterfall) of the Fiume Elsa (Elsa River) in the hill town of Colle di Val d'Elsa. The changing courtyard light reflects on the water-filled glass cylinders of the sculptures in vertical rivulets, generating a subtle dynamism in the space alongside the lace-like fronds of two tree ferns lifting in the breeze. Paired with the stone architecture and the foliage of the in-house plant collection, the glass cascades reference the spring-fed fountains of a nymphaeum in a grotto, a type of semi-natural shrine that became a feature of Italian gardens in the 16th century.

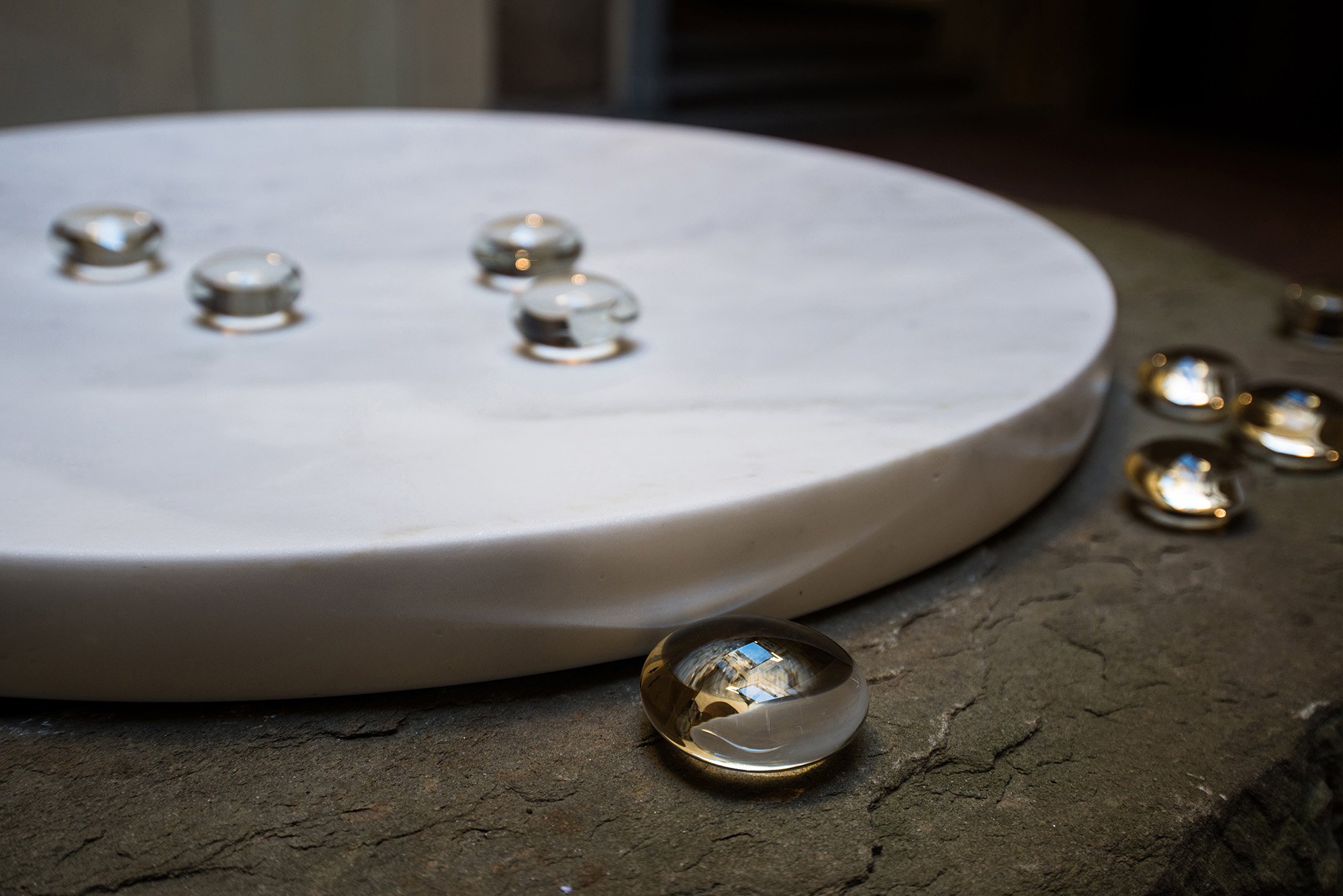

A series of small, solid glass optical sculptures were placed around the marble pool, along the edges of the stone floor, and on the plinth of the 17th-century marble statue of Hercules and Iole (by Florentine sculptor Domenico Pieratti) like seeds cast from an unseen tree. The organic form of the glass sculptures is a reference to a memory of collecting fallen chestnuts in autumn in the hills of Valdicastello, Tuscany, with sculptor and marble carving teacher Kyle Ann Smith. The handmade gravity-formed glass pieces were introduced into the space as propagative talismans of the temporal phenomenon from which a garden begins—light. Titled light seeds, the flameworked glass forms cultivate light, highlighting shadowed spaces and reflecting the courtyard's Renaissance columns and arches, delicate plant life, and passing clouds.

During the Italian Renaissance, the understanding that a garden could be a work of art emerged for the first time in modern history. In the Renaissance garden, as described by Italian historian Claudia Lazzaro, the formal is "juxtaposed with the natural. This basic contrast between formal and natural, art and nature, provides the key to its meaning" (1). The distinctions between interior and exterior spaces softened and artistic ideas were expanded and transmitted via plant life, water, and stone, often with "unifying themes which allegorize[d] the passage of water in nature", as described by Lazzaro in her book, The Italian Renaissance Garden (2). She writes that the 16th century was influenced by "A dialectic, a flow back and forth" that "best characterizes the relationship between art and nature, especially in gardens". The intrinsic elemental forces at play in gardens "reflected the belief in the correspondence between things visible and invisible which was central to Renaissance thought". This essential unravelling of understandings of nature and art continues in the contemporary garden, where ways of being and ways of creating are revealed and implicated in "the ripples of our actions, as well as of our visions" that, in time, "reverberate right at our feet, directly in our gardens", as explained by Italian author and environmental philosopher Serenella Iovino in "The Reverse of the Sublime: Dilemmas (and Resources) of the Anthropocene Garden" (3). A garden is the embodiment of a released idea, a space housing a sensory language in congruence with the temporality of place, generating an earthly essence with unhurried, poetic ease.

The collection of plants inhabiting the courtyard of Palazzo Galli Tassi includes two tree ferns, an ancient plant group that pre-dates dinosaurs, with a number of its species native to Australia; the significance of these plants became familiar to Abel during past projects in Australia stemming from remote bushwalking and cave visits in New South Wales

Like the discovery of a garden, the experience of art can feel like an arrival—one travels to and moves around (or within) an artwork, composing perspective with a physical presence as a visitor or, in some cases, a participant. In her book, The Japanese Garden, author Sophie Walker explains that a "garden encourages us to engage in time-based progress, in continuity and subtle change" (4). In the same way, art can invite visitation in time and place. Reflecting the palazzo environment and the transforming sky above, the works of Light Garden consider the intimate space of the courtyard as intrinsically interconnected with the expansiveness of the exterior world that reveals and enlivens it: the light of the sun rising and setting; nighttime shadows beneath moonlight; and seasonal cycles of rain.

Light Garden was developed out of a more than decade-long artistic practice that Abel calls conceptual gardening, where, tending to the duality of fragility and timelessness, the unity of a garden is realized as a work of art. Here, surfacing and resurfacing from the beginnings and endings of the diurnal cycle, a garden is a mirror, a reflection of the light it receives.

Tramonto (sunset)

One of the terraced cascades at Cascata del Diborrato (Diborrato Waterfall) of the Fiume Elsa (Elsa River) in the hill town of Colle di Val d'Elsa, Siena, Italy, 2022.

Photo by Karen Miranda Abel.

Collecting water from the terraced cascades at Cascata del Diborrato (Diborrato Waterfall) of the Fiume Elsa (Elsa River) in the hill town of Colle di Val d'Elsa, Siena, Italy, 2022.

Photo courtesy of Martino di Napoli Rampolla, Numeroventi.

Karen Miranda Abel working on the marble reflecting pool at the marble workshop and studio of Kyle Ann Smith in the Tuscan hills of Valdicastello, Pietrasanta, Italy, 2022.

Karen Miranda Abel working at the marble workshop and studio of Kyle Ann Smith in the Tuscan hills of Valdicastello, Pietrasanta, Italy, 2022.

Intro. Calvino, Italo. Collection of Sand: Essays. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013, p. 170.

1. Lazzaro, Claudia. "The Villa Lante at Bagnaia: An Allegory of Art and Nature." Art Bulletin, vol. 59, no. 4, 1977, pp. 553-60.

2. Lazzaro, Claudia. The Italian Renaissance Garden: From the Conventions of Planting, Design, and Ornament to the Grand Gardens of Sixteenth-Century Central Italy. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990, pp. 8,10.

3. Iovino, Serenella. "The Reverse of the Sublime: Dilemmas (and Resources) of the Anthropocene Garden." RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment and Society, no. 3, 2019, p. 5.

4. Walker, Sophie. The Japanese Garden. Phaidon Press, New York, 2017, p. 6.

Numeroventi, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Ontario Arts Council are gratefully acknowledged for supporting this project